Artist Interview 110: Catherine Heard

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

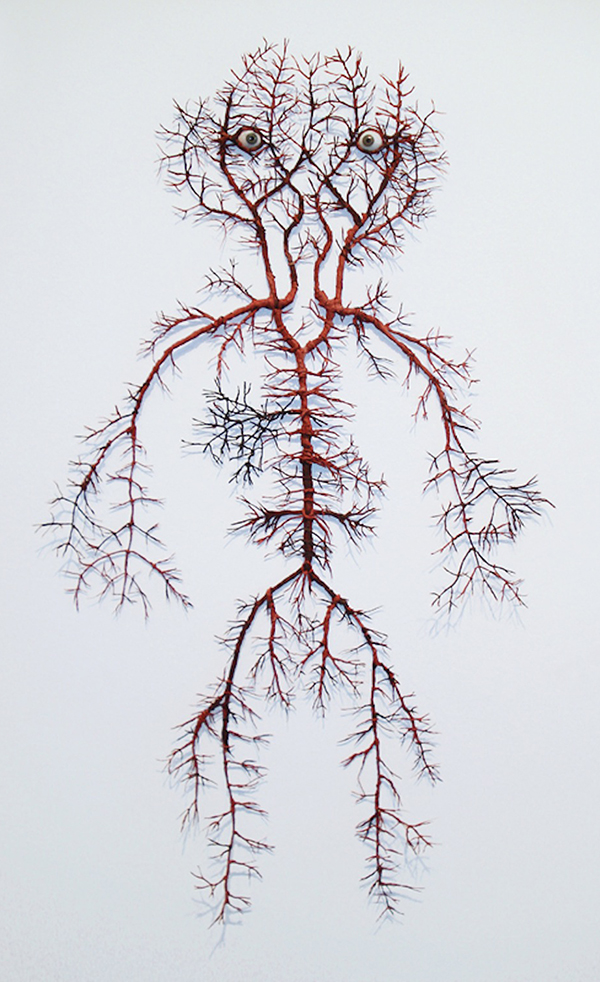

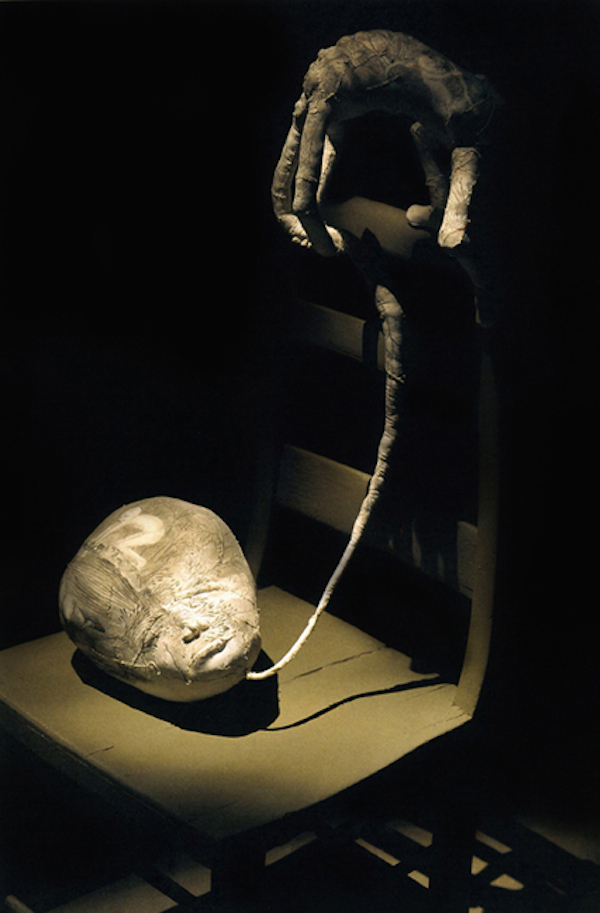

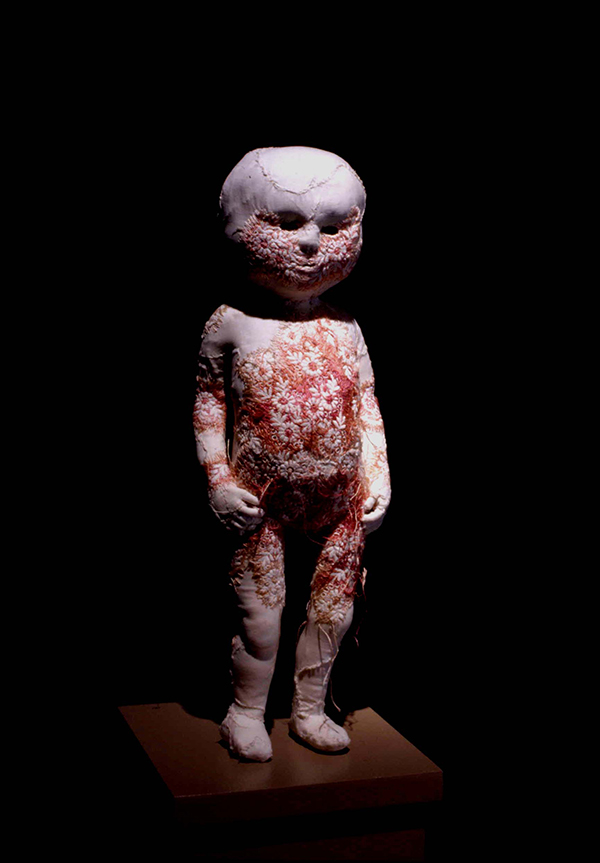

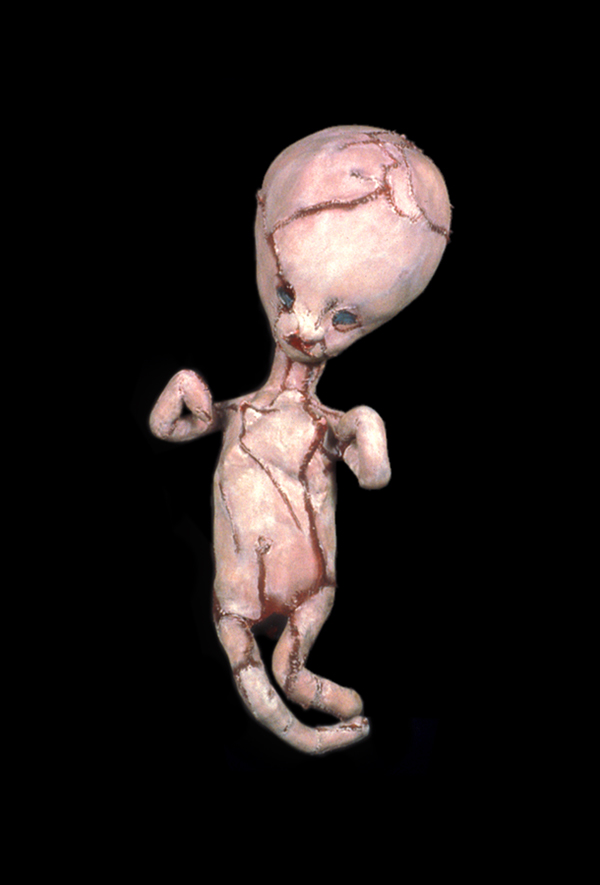

Simultaneously attractive and repulsive, Catherine’s works delves into primal anxieties about the body. When I took my first fabric sculpture into the classroom, she noticed that people wanted to look closely at it, but they didn’t want to touch it. She explores themes through images of the female body, the monstrous body, the doppelgänger, the abject body and the dead body.

Tell us about your work?

I have been interested in the history of the body as a site of anxiety throughout my career, from the early 1990s to the present. I have explored this theme through images of the female body, the monstrous body, the doppelganger, the abject body and the dead body.

I believe the choice of technique and materials is integral to structuring the meaning of images. I have researched historical techniques extensively and, over the years, have incorporated medical wax casting (moulage) and modeling (écorché), oil–based and water–based marbling, felting, Victorian hair art, and embroidery into my practice.

Previous World of Threads Exhibitions

Catherine Heard exhibited in the 2014 Festival exhibition Solo Shows.

Where do you get your inspiration?

When I look through old sketchbooks I can often see the germ of the idea I'm currently working on appearing two, five or even ten years earlier. This suggests to me that inspiration is a constellation of fragments accumulated from a wide range of sources over a period of months or years. The sources that inform my work include objects in museums, historical techniques, articles and books I have read, historical and contemporary works and personal experiences.

I didn't identify Surrealism as an influence until it had been pointed out to me several times.

What specific historic artists have influenced your work?

In terms of what others see in my work, the most common reference to come up is Surrealism. The strange thing is that I didn't identify Surrealism as an influence until it had been pointed out to me several times by several curators and critics. Initially I resisted the idea that there was a connection. In retrospect, I think their judgment was spot on. It wasn't an influence I was conscious of at the time but, looking back, I think it was one of the predominant influences for my generation of artists. I can pick out the Surrealist influence much more strongly now when I look retrospectively at the work I was making in the 90s. And, when I compare it with the works younger artists are making today, I notice that their work seems to have been more strongly influenced by conceptual practices and Pop Art than the work of my generation was.

A few years ago, I finally made a long over due homage to the Surrealists by creating a series of collages that amalgamated images from a book on doll collecting with images from children's encyclopedias that were printed in the 1920s. The original collages were relatively small, but I also digitized them and had them printed on metallic paper at a larger scale. It would normally be against my aesthetic to scan a work on paper and to reprint it, but in this particular case, it felt right to make two versions. One is true to its roots, and the other looks backward in time from the present.

What specific contemporary artists have influenced your work?

I believe that we are most strongly influenced by the artists who are closest to us. Being a member of the Nether Mind collective in the 1990s had a major impact on my work. The conversations I had in the early years of the collective with John Dickson, Lyla Rye, Max Streicher, Mary Catherine Newcomb, Greg Hefford, Tom Dean and Reinhard Reitzenstein helped crystallize my ideas about sculpture and installation art. Recently, after a hiatus of seventeen years, Nether Mind began exhibiting together again. The first exhibition we did after our 'resurrection' was at St. Anne's Anglican Church in Toronto in October 2012. The second was at the University of Waterloo Art Gallery in January 2013. We're currently working towards a third exhibition that will take place in September 2014 in Toronto.

What other fibre artists are you interested in?

I am a big fan of Angela Silver's work – especially her book works. I especially like the works she has made with flocking, Night Writing and Handbook of Poetics. In each book, an astronomical star map is flocked over the original text. One of the things that intrigued me about these works is that the flocked dots interfere with conventional reading of the text, but augment and transform it poetically. The works are visually austere, but rich in associative content.

I own one of Noelle Hamlyn's abstract works made from Japanese tissue paper that is sewn and then meticulously burned to create cell-like patterns. It is a subtle piece that changes dramatically depending on how the light strikes its surface. Noelle has a meticulous eye for detail, but rather than the detail tightening up into geometric shapes, the abstract patterns remain loose and organic.

Recently I stumbled across Anna Wieselgren's series, Electoral Ink online, and it reminded me of her earlier piece, (dis)location, which was sewn from used bed sheets from a refugee centre for Tibetans in New Delhi. The colour of the balls is a subtly faded range of blues tinged with violet. When Anna originally told me about the piece, she talked about the experience of making the work at the refugee camp, and about the children playing with the balls. The original installation was in a building at the camp that had walls painted intense green about half way up their height and lit by large windows. The installation transformed a pre-existing space and simple materials that were at the end of their useful life into a work of art. It was very simple, but evoked complex ideas about the space, people and displacement.

I think what all of these artists have in common that I respond to, is their sensitivity to materials, and their reserve. The works have a minimal aspect, in the sense that the artists have stripped away all unnecessary elements and duplications of information. To complete the work, the viewer has to read into it using their personal history and knowledge. The advantage of this kind of work is that it never get old – you are always discovering nuances of meaning and details you hadn't noticed before.

Tell us about your training, how it has influenced you and how you have applied what you have learnt.

I enrolled at the Ontario College of Art in 1985 in the General Studies department, which allowed me to take courses from any discipline. In my second year, in addition to taking painting and drawing courses, I also took a papermaking course, and made my first fabric sculpture out of old paint rags and newspaper. Oddly, I know that this piece was made on a Sunday, because I wasn't able to buy any materials that day and ended up using rags that were lying around the studio. The piece wasn't made for a particular course, but when I took it to school, I noticed that people had a peculiar reaction to it – they wanted to look at it closely, but if I tried to hand it to them, they didn't want to touch it. This simultaneous reaction of attraction and repulsion fascinated me, and I began to try to elicit it consciously in other works. Realizing that an inanimate object could elicit a visceral response was perhaps the most significant thing I learned that year, and that dynamic is still present in most of my work.

After my third year, which I spent in OCAD's Florence program in Italy, I made the decision to return to school part time so that I could work enough hours to afford a studio. In retrospect, this was probably the best decision I could have made, as I had begun showing before I graduated. This made the transition from being a student to being an artist seamless. It liberated me from the temptation to take a full time job after I graduated, or to take a teaching degree after finishing at OCAD – which was what my parents were lobbying for me to do at the time. In retrospect, one of the most important things I learned during my undergrad was about the ongoing determination that one needs to survive as an artist. The other was realizing how much I enjoyed learning new materials and techniques, which has become a mainstay of my practice. Almost every project I take on involves developing a new skill or technique.

Realizing that an inanimate object could elicit a visceral response was perhaps the most significant thing I learned that year, and that dynamic is still present in most of my work.

Please explain how you developed your own style and how do you describe your art to people?

I'm not certain if I have an easily identifiable style. I work in such a wide range of media that a work in one series can look radically different than the work in another series. I would describe my work as being bound together by a series of recurring imagery and themes, rather than a cohesive style.

The meaning of the work, in some senses, is out of my hands once the work leaves the studio.

What is your philosophy about the Art that you create?

In my experience, making art is like groping around in the dark trying to solve problems or answer questions. I can articulate the question, which is the beginning of making something, but in making the object, the question always seems to become more complicated and convoluted, and what I produce sometimes doesn't even end up addressing the problem that initiated the process. Although the work often is initiated with a personal experience, the unexpected discoveries that take place during the process, often displace the original impetus for the work and meaning sometimes shifts radically as I work through imagery and ideas. When the work is finished and I look back on it after months or years have passed, I am finally able to see it more as an outsider would see it, and – perhaps not surprisingly – I discover that there are interpretations that I didn't consciously intend, that seem clear in retrospect. Viewers, critics and writers all bring their own interpretations to the work as they read it though their personal experiences and the specific contexts of time and place. The meaning of the work, in some senses, is out of my hands once the work leaves the studio. There is a certain liberation in feeling that the work has the ability to speak for itself, and that I don't have the sole responsibility of determining its interpretation.

How did you initially start showing your work in galleries?

In the early 1990s the economic recession meant that there were far fewer commercial galleries than today. Like many Toronto artists of my generation, my experiences exhibiting in non-traditional spaces with artists' collectives had a greater formative impact on my career than exhibiting in the traditional gallery system did. Although I did also exhibit in artist run centres during the 1990s, the exhibitions that were most memorable for me were with Nether Mind, Duke-u-menta and Round Up. Nether Mind and Round Up took place in vacant industrial spaces that we could rent cheaply, and Duke-u-menta took place in the empty rooms above the Duke of Connaught Tavern. These atmospheric spaces were ideal for installation art.

When working on location with an installation, how much do you improvise?

Because my work tends to be labour intensive and the sculptures are time consuming to execute, the works – including the floor plan – are usually developed many months before the exhibition. Although I may tweak a few things when I am installing, it would be rare for me to make major improvisations at this time. When a work conceived for one space is exhibited again in a different space, I rework the floor plan and occasionally change elements of the work to suit the new space. For example, in the original version of Confessional, which was developed for one of the Nether Mind shows in a warehouse with extremely high ceilings, the sculptures were accompanied by a life-sized photo of a wedding dress that was mounted high up on a wall. In later exhibitions, the vertically oriented life-sized photo was replaced by a much smaller, horizontally oriented photograph of a wedding dress that was "twinned" in Photoshop to mimic the form of the conjoined twin sculpture that was the centre of the installation.

What is the most interesting thing to you about the world of fibre art?

It is an enormously varied field of practice that has ties both to the ancient past and to the future of technology, and embraces artists who work in an incredibly diverse range of media. People sometimes mistakenly believe that fibre art is limited to the traditional crafts like weaving, sewing and dyeing, when in fact it is quite the opposite. It challenges the artist to take the concepts gleaned from traditional practices, and to bring them into the present – even to project them into the future ad innovative technologies become available.

What do you consider to be the key factors to a successful career as an artist?

It depends on how you define success. After twenty years I still don't make a living solely from my work as an artist, but I am still making and exhibiting art after twenty years. By that definition, probably dogged stubbornness is the key factor … and maybe having a bit of a masochistic streak in my nature.

What interests you about the World of Threads festival?

The Festival brings together a critical mass of artists and their works to create a snapshot of contemporary fibre art practice. It gives viewers a window into an area of artistic practice they may not have been aware of, and it gives fibre artists the opportunity to see what others in their field have been up to and to exchange ideas.