Artist Interview 90: Temma Gentles

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

(Temma Gentles: 1946-2023) The majority of Temma’s work was religious commissioned pieces, which reside in churches and synagogues throughout North America, and for home and personal use. She considered that the essence of all her work was in bringing stories to life. We were glad to have had the chance to interview Temma back in 2013. Temma's major work "Torah Stich by Stich" was fully realized in 2019 at the Textile Museum of Canada in Toronto.

Tell us about your work

The majority of the work I produce is commissioned for religious environments, both for congregations and for home and personal use. The commissioned pieces are in churches and synagogues throughout North America. Several other pieces have been purchased for museum collections.

I also do a substantial amount of teaching, mentoring, organizing arts projects, and volunteering. I was Event Committee Chair of Toronto Outdoor Art Exhibition for much of the past decade, and I'm currently treasurer of the Volunteer Association of the Textile Museum of Canada. It's difficult to turn down these interesting roles, but they do take time and energy.

I am presently Artist-in-Residence at Holy Blossom Temple, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. This long-but-indefinite-term position is a new one for the Temple, and with little precedent in other institutions. They have given me a funky space as a studio, and I give them a certain amount of programming. It is a win/win situation, and one I trust will be enriching on many levels.

Where do you get your inspiration?

The essence of all I do is bringing stories to life. These emerge from several sources.

1. Biblical narrative and symbolism, which I tend to use in a metaphorical way, rather than for their illustrative value.

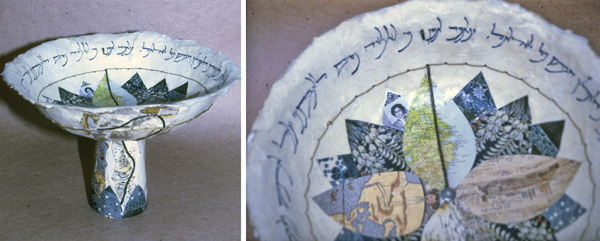

The whole assembly illustrates Zechariah's dream that at the end of the Babylonian exile the lights of the Temple's menorah in Jerusalem would be rekindled with oil oozing from two olive trees into a seven-spouted vessel. The right-hand photo shows a well-known illustration of this dream. The layers surrounding the scroll progressively dematerialize and thereby wrap it in radiance [Psalm 104:2], signifying that God's spirit illuminates our lives from the natural world (the piece is wired to be solar powered) as well as from the inspiration of wisdom.

![08-hidden-and-revealed-temma "Hidden and Revealed", collaboration with Dorothy Ross, fabric and beadwork construction. Commissioned by Women for Reform Judaism for the Golomb Chapel at URJ (New York NY). Just as the tightly structured wedding kimono has, surprisingly, a crimson silk lining, so it is a joy to discover delights within the traditional and sometime formulaic words of Torah.This mantle wraps the scroll in an assembly of square parcels. In Buddhist and Shinto belief squares connote completeness and balance. Silk-screened on some squares are texts referring to God's truths being both hidden and revealed. The complete texts are scrolled into the breastplate, like private treasures within a locket. This piece is fastened with rows of five pearls, five being a number associated in Judaism with the senses, creating, and protective hamza. The obi [sash] area holds a beaded yad [pointer used while reading the scroll].](https://worldofthreadsfestival.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/08-hidden-and-revealed-temma.jpg)

2. Traditions and life-cycle events also create an opportunity for story telling, as do the personal stories of my clients.

An early "watershed" piece was the wedding canopy for Temple Emanu-El in Toronto (which won an award from the Interfaith Forum on Religion, Art and Architecture). When Karen Lester became a bat mitzvah, she asked guests in lieu of gifts to donate toward the creation of a chuppah for the synagogue in memory of a family friend.

"What did you like about him?" I enquired. She answered that he loved to sail.

Through research, I discovered that ritual law does not limit a wedding canopy to the standard rectangular, four-poled shape. And so the chuppah was fashioned as three layers of triangular, suspended "sails." I turned to a sail-maker for guidance, buying grommets, turnbuckles and other hardware from him. That's part of the adventure. There's always something I don't know how to do.

Onto blue polyester drapery sheers, I appliqued a trail of hand-painted stars and words from the seven wedding blessings. The chuppah is both low enough for the bride and groom to touch the bottom "sail" and vast enough for the congregation to sit under.

Post-script: 15 years later Karen was married under the chuppah and expressed the significance and comfort of "remembering someone so important in my childhood as I was going to move forward with my life."

![09-tik-open-temma "Layers of Light' Tik [hard Torah case] and Neir Tamid [Eternal Light], Collaboration with Dorothy Ross, 76 x 36 x 25 cm (30 x 14 x 10 in), Beads, threads, wood, fiberglass screening, LEDs, glass, beading, embroidery, construction, aluminum structure: James Maxwell; lighting wizards: Dr. William Gentles, Dr. Roel Wyman. Photo on left: Russ Jones; photo on right: Paul Kay.](https://worldofthreadsfestival.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/09-tik-open-temma.jpg)

3. The fabrics themselves.

The Spertus Museum in Chicago conducted a biennial competition that invited any artist worldwide to create a specified ritual object. Dorothy Ross and I decided to enter the competition (which had a cash prize of $10,000 in addition to distinctions heaped on the winners). We had two ideas that grew from the premise that the words for Torah, wisdom and understanding are feminine nouns in Hebrew; and so we should be dressing the scrolls as a woman, rather than (as was more typical) as a high priest. We vacillated between a Japanese wedding kimono and a Baroque Italian bride. On our shopping expedition we fell in love with a lush velvet... and that determined our direction. We used stitching and beading techniques to playfully recreate the layerings and showy linings of Baroque costume. A beaded locket serves as a breastplate and an amulet.

A few years later Dorothy and I got to make a kimono mantle for a Torah scroll commissioned especially for Women of Reform Judaism (WRJ). When not traveling to WRJ chapters, the Torah and mantle rest at the Union for Reform Judaism's Golomb Chapel in New York City. [Left side of image below]

The other mantle [right-side above] is constructed from five panels of crazy quilting, representing the five books of the Pentateuch. The mantle's irregular ascent from reds and scarlets to an amalgam of blues symbolizes the human struggle from earthly to spiritual that is present throughout the Torah.

![07-spertus-comp-temma She is a Tree of Life", collaboration with Dorothy Ross. Winner of the Spertus Judaica Prize. A variety of fabrics, trims, and beads; appliqué, beading, construction. 99 x 56 x 33 cm (39 x 22 x 13 in). Collection of Philip and Sylvia Spertus. Photo: Thomas Nowak, courtesy of Spertus Museum, Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies (Chicago IL). Because 'torah', 'wisdom', and 'understanding' are feminine nouns in Hebrew we dressed the scroll like a 17th century Italian bride. Israel became God's bride by accepting Torah at Mount Sinai. This concept is elaborated in several symbolic ketubot [wedding contracts] for Shavuot [Pentacost].](https://worldofthreadsfestival.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/07-spertus-comp-temma.jpg)

4. Meandering through life.

As Tennyson's Ulysses says:

…all experience is an arch wherethro'

Gleams that untravell'd world, whose margin fades

For ever and forever when I move.

Why did you choose to go into fibre art?

I'm not sure I consciously made that choice. My grandparents owned a ladies' wear store in the Beaches, and we lived close by. She had style, and he made everything fit perfectly. They taught me to knit and sew and the importance of meticulous craftsmanship, and I always loved the look and feel of fine fabrics.

I did not study textiles at OCA (now OCAD University), except for silk-screening. I might have been just as happy working in wood or metal or even plastics, and I still seek opportunities to work with artists in other media. My commitment is much more to a thoughtful and creative use of space and time, rather than to a particular craft.

![12-shaarei-shomayim-comp-w-birds-temma Wedding Canopy for Shaarei Shomayim Congregation, Toronto ON, cotton, silk and wool on bronze polyester scrim; appliqué, collaboration with David Hunt (metal artist), Ken Dubblestyne (bird sculptures) and Mark Dougherty (lighting), 244 x 244 x 350 cm (96 x 96 x 138 in), photos: Paul Kay. Designed to be used either in the midst of the congregation or on the bimah [chancel], this bronze and gold dome-shaped chuppah [wedding canopy] becomes a semi-transparent sky hovering above the marriage ceremony. A complex network of stars emerge from the light of God's blessing. "The text, 'I will betroth you to me forever', is repeated inside and outside the chuppah in all four directions. Four sculptured birds celebrate.](https://worldofthreadsfestival.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/12-shaarei-shomayim-comp-w-birds-temma.jpg)

What other mediums do you work in, and how does this inform your fibre work?

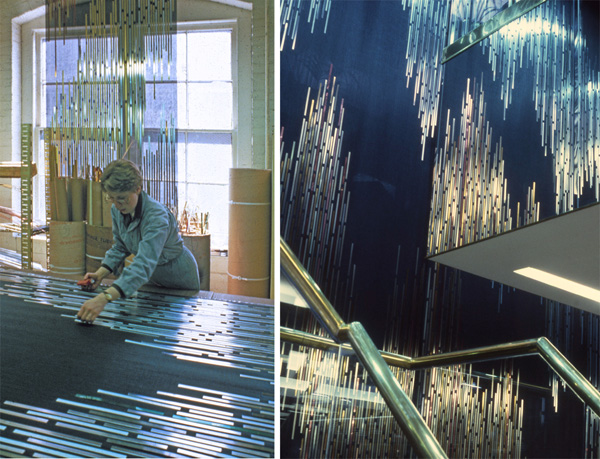

Sometimes fabric just doesn't seem the right solution. For example, with the Ark Gates for Temple Shalom, I was actually hired to do a fabric curtain, but the site kept suggesting something tougher. I ended up designing a giant "paper cut" of cold-rolled steel layered over a collage of handmade Japanese paper. Water-jet cutting was quite scarce and expensive at the time, and consumed the entire budget. Nevertheless it worked out magnificently on both professional and personal levels. The story still circulates in the congregation that because they couldn't pay me enough, they gave me the President. Paul and I have been happily married for the 16 years since we finished the project.

In several architectural-scale projects, such as the Wedding canopy for Shaarei Shomayim, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, lighting is crucial to the success of the textile art, and so I worked with a lighting designer. It was also fun in that piece to contract the head of props at Stratford Shakespearean Festival to make me four "birds with attitude" to celebrate the couple as they stand under the glowing dome of stars.

Although I always pay the "trades" what they ask (and I know that they are often kind to me in their pricing because of the fixed project budget), it is usual that they charge at least double what I hope to get for my time. No one who works in textiles or beading will be surprised at how long it takes or the cost of beautiful materials that will withstand communal use; however, the public seldom understands, and that can be an issue.

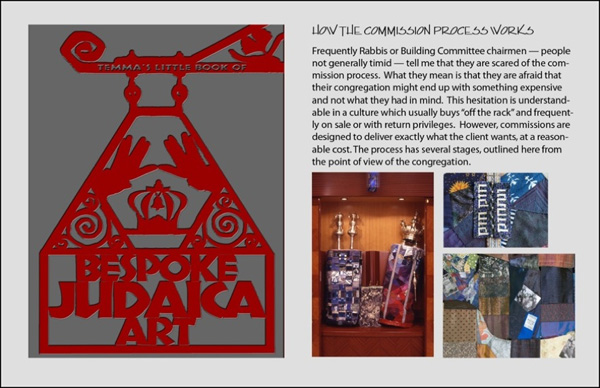

To that end I wrote a pamphlet to educate potential clients on the commission process. Thirty years ago Jean Johnson organized more than one event at Harbourfront to highlight this design area. It's an ongoing educational need, especially in a society increasingly unfamiliar and uncomfortable with the concept of "bespoke" goods.

What specific historic artists have influenced your work?

I truly wish Paul Klee were still alive and I could thank him personally for what he has taught me about colour. On more than one occasion, I have turned to Klee for inspiration on how to make a rather mundane or even dissonant palette on site sing with excitement and harmony. I don't think, left to my own devices, I would have thought of introducing the electric blues or fuchsia into the palette of this sanctuary... but how they sing!

![14-shoshanan-emma Shoshanah [Lily] mantle for Temple Beth Am (Seattle WA), A variety of fabrics, trims, and beads; appliqué. The recently widowed donor wanted to express the joy of Shabbat, rich Moroccan colours, the flowers she saw when she met her husband on the mission to Israel. "Shoshana", the lily, is perhaps the quintessential flower of Israel, and certainly central to the Song of Songs and much Hebrew poetry.](https://worldofthreadsfestival.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/14-shoshanan-emma.jpg)

What other fibre artists are you interested in?

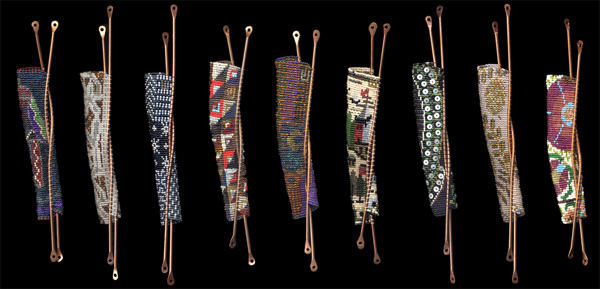

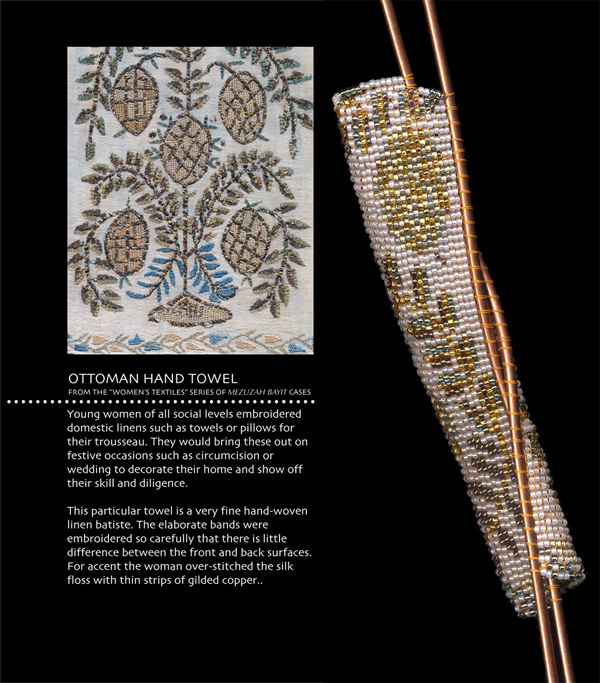

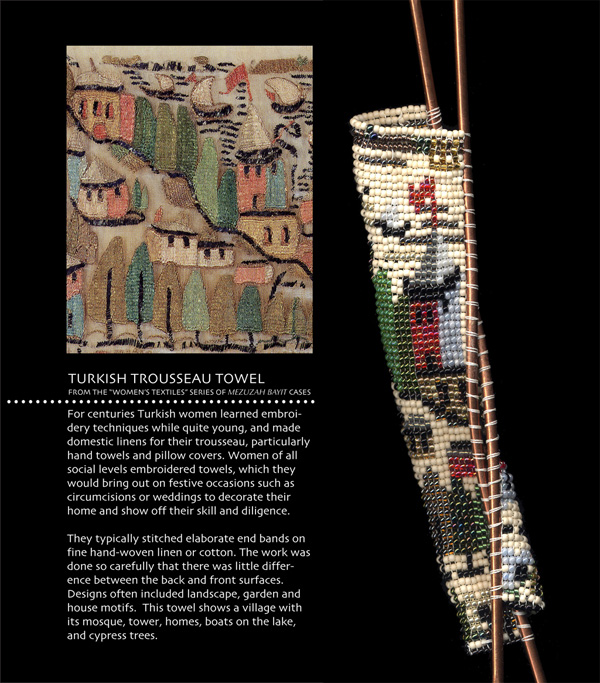

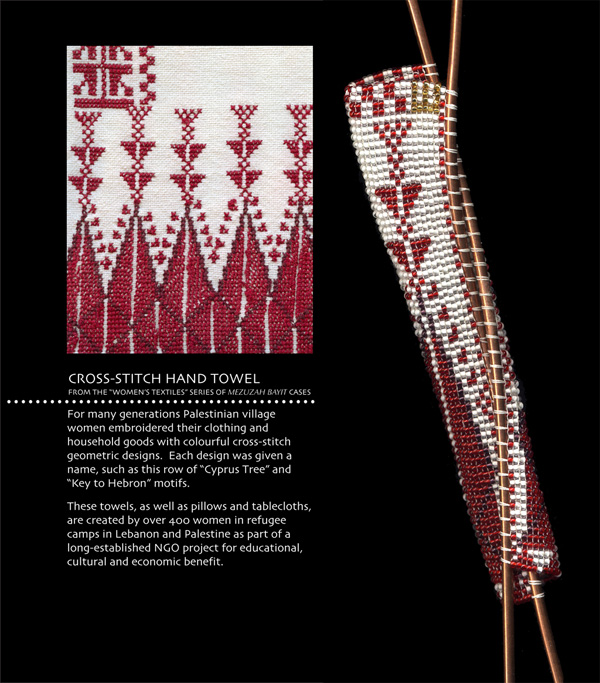

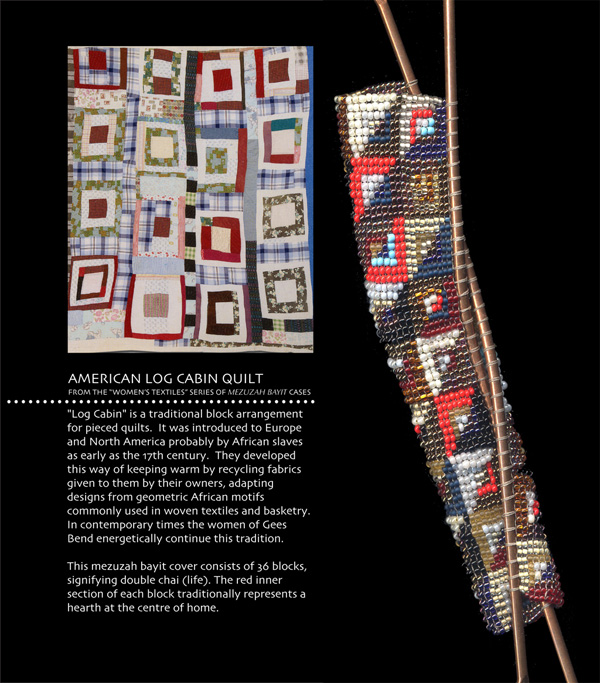

Textiles created by women are an ongoing interest, partly because these capture the authentic patterns of each people. It also seems that wrapping oneself or children in cloth is a fundamental way of protecting, teaching, and creating spiritual space. This interest is shown, for example, in the bead-woven mezuzah cases that are used for protecting the prayer mounted on the doorpost of Jewish homes to raise our awareness of proper thought and behaviour each time we enter or leave.

These mezuzah cases are part of a series inspired by women's textiles from around the world. The form literally embraces the scrolled prayer inside, and each design is quite clearly based on an ethnographic source.

Is there someone who has made a difference/impact on your work?

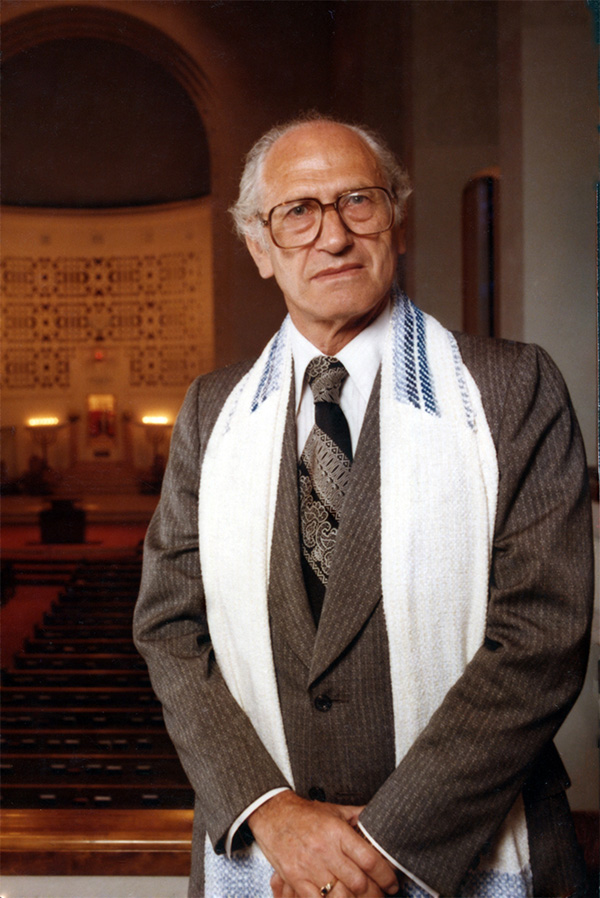

Distinguished Rabbi W. Gunther Plaut was the first person to commission me to create a religious textile: a prayer shawl/tallit for himself. It was an "aha" moment to realize I could bring together three areas of great personal meaning: literary study, Judaism and making things. And his Torah commentary, which was published a few years after this, continues to be a primary research tool in most of my projects.

My academic mentor, Northrop Frye, expressed himself most often in simple words and straightforward sentences. The profound impact of these derived from his wealth of references and allusions acquired from broad enquiry, deep understanding and lengthy living. He was also my neighbour and willingly discussed raccoons in the garbage. I do not in any way compare myself with Professor Frye intellectually, except to claim that his manner of plain speaking and his concept of the educated imagination have inspired me throughout my life and work.

When did you first discover your creative talents?

I can't pinpoint an awakening of creativity or quantify talent, but I do know that I have enormous curiosity. Despite the fact that I grew up quite poor in Toronto we always had some art supplies, and my mother made sure we had exposure to the visual and performing arts. Among those early experiences were Dalcroze Eurhythmics and Saturday Morning Clubs at the Royal Ontario Museum. It is fascinating that so many people who have become luminaries in the arts (for example, Margaret Atwood and Tim Jocelyn) participated in those programs and have acknowledged them as fundamental.

How has your art changed over time?

The process has evolved from being purely my own work to pieces involving significant collaboration. Collaboration is not an approach I can – or want to – use in all projects, but I embrace the opportunity when appropriate.

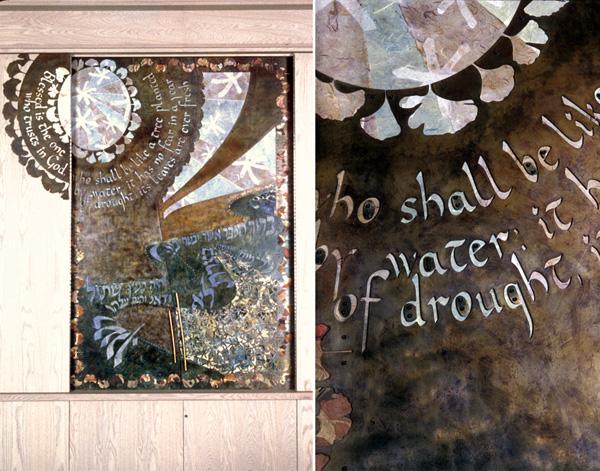

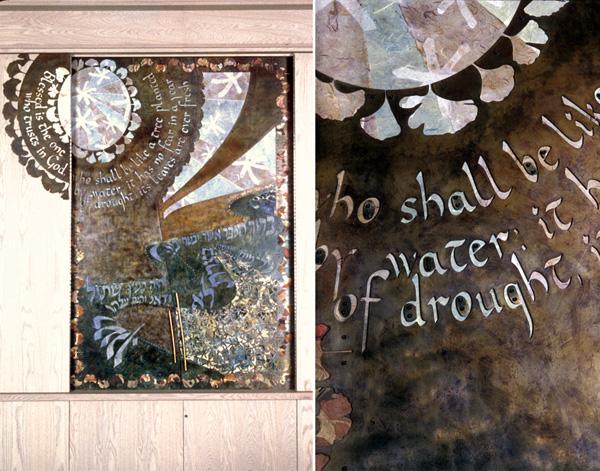

I have already acknowledged the important role of those who have skills I lack – such as metal and glass artists and lighting designers – in realizing my vision. However, collaborations with beader Dorothy Ross or calligrapher Laya Crust (two examples) have produced pieces that are more potent than the sum of our individual ideas and skills.

I have always enjoyed being a "midwife" to the work of others; for example, the conceiving, designing and directing Sukkah installation of the Pomegranate Guild of Judaic Textiles (which I helped to found over 30 years ago and is still going strong), or the Torah Stitch By Stitch (see below). www.pomegranateguild.ca

More of my recent work is conceptual; for example, a series of hooked rugs that reflect both real and imaginary stories and songs of Newfoundland. These grew out of a wonderful residency a few years ago in Brigus, in the Conception Bay, Newfoundland, along with the opportunity to meet artists and storytellers there, and to handle the textile collection at The Rooms.

![29-katagami-Indigo-w-text-temma Kata-gami Ketubah [wedding contract], "Giclée print on archival paper, 71 x 46 cm (28 x 18 in). Kata-gami is the ancient Japanese art of cutting stencils that are used for printing garments and household textiles. The klaf [parchment] stencil here has become a paper cut divided into quadrants with patterns suggesting the Elizabethan four elements of earth, water, air and fire. These sections are further sectioned into 18 (chai) rays of light surrounding the ketubah text to wish the couple a long and blessed life together.](https://worldofthreadsfestival.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/29-katagami-Indigo-w-text-temma.jpg)

What project has given you the most satisfaction and why?

I could no more answer this question than I could declare which are the favourites among my children or grandchildren. There have, of course, been watershed pieces, such as the wedding canopy for Temple Emanu-El, or the window coverings for the McDonalds flagship restaurant at University and Dundas, or the series of conceptual works created from the Geniza (huge bins containing damaged religious items) in Jerusalem.

Some projects have resulted in work that I consider excellent in retrospect, although the commission process at the time was extremely problematic.

When people see my work in a sanctuary, I'd like them to feel it's always been there, that it belongs.

What is your philosophy about the Art that you create?

When art is content-heavy (as with Biblical narrative) there is always a danger of pedantry. I try to integrate the medium and the message often through symbolism. I also respond to the architectural space and the way in which the piece will be utilized within the "choreography" of ritual. Each project has its own organizing principles. When people see my work in a sanctuary, I'd like them to feel it's always been there, that it belongs. At the same time, I'd like them to be drawn to it to examine it more closely in terms of content and aesthetics.

![23-how-beautiful-temma Pomegranate Sukkah, created by approximately 60 members of Pomegranate Guild of Judaic Textile (Toronto ON). Wood, fabric, thermal veil, embellishments; many techniques. 8' x 8' x 8' (248 cm cube), photo: Neil Seigler. During the autumn harvest holiday of Sukkot [Booths] it is customary for families to eat meals in the sukkah, and also to welcome guests each day. Despite its laborious craftsmanship and apparent delicacy, this sukkah was made to withstand outdoor use. This installation was designed as the first group project of the Pomegranate Guild, and has been shown in several museums and galleries.](https://worldofthreadsfestival.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/23-how-beautiful-temma.jpg)

What are you working on now?

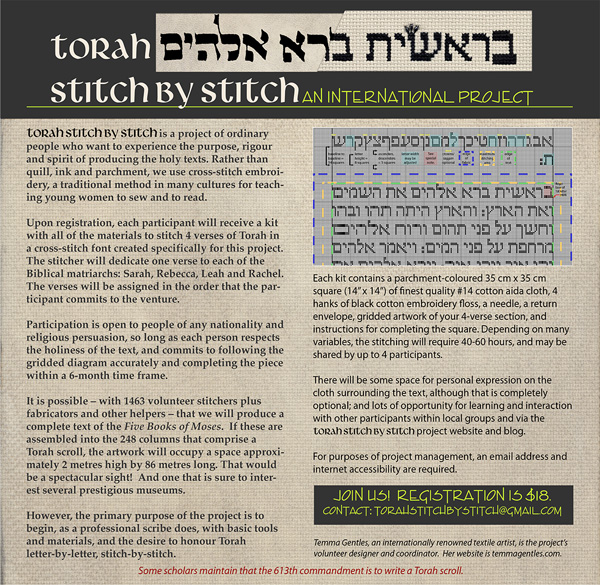

In addition to a scholarly lecture series on Creating Spiritual Space and several commissions to be completed within the next few months. 14. I've just launched an international project that comes purely from a "crazy" idea I had. And yet people of all faiths all over the world are responding enthusiastically. Only 2 months since the launch we are 150 stitchers in 7 countries. The possible magnitude of it gives me chills of both excitement and terror. To paraphrase Ray Bradbury, I feel that I've jumped off a cliff hoping to grow wings before hitting the ground. torahstichbystich.temmagentles.com

![26-tales-from-the-geniza-temma Tales from the Geniza [place to collect damaged/discarded sacred or heretical texts]: Mrs Harry Goldman. Mixed media; objects from the Jerusalem and San Francisco genizas, photos: Paul Kay.

An ongoing series of works that juxtapose and creatively intervene in objects from several geniza sites around the world to tell their [fictional] stories. The pages from the New York Daily Mirror (December 27, 1937) were used as wadding behind the right-side commandments tablet. For example:

"Although the provenance of most geniza objects is not known, this group is clearly identified. Harry Goldman died in 1936 at age 72 when he was unable to get out of his house during a fire that started when he was trying to surprise his wife with dinner. Mrs. Goldman arrived home just after the fire crew put out the flames in the entrance and were searching for Harry. As she followed them into the house, she grabbed his water-soaked tallit [prayer shawl] bag on the hall table and clutched it throughout the tragically unfolding ordeal. On Harry's first yahrzeit [anniversary of death] Mrs. Goldman presented the congregation with a Torah mantle. It was only after this well-used cover was retired to the geniza that the full extent of the gift was revealed: Mrs. Goldman, a member of the local Pomegranate Guild, had obsessively embellished the tallit's water stains, embroidered a very personal message to Harry, created a hidden pocket out of the tallit bag, and sewn it into the lining of the mantIe. This way Harry could continue to be in regular attendance at the services he so loved."](https://worldofthreadsfestival.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/26-tales-from-the-geniza-temma.jpg)

What interests you about the World of Threads Festival?

Gareth wrote me a lovely rejection letter, saying something to the effect that most of the work submitted by other artists seemed to fall naturally into groups of subdued colours with somber themes . . . and mine was just too colourful and cheerful to fit. It didn't feel entirely like a compliment. However, when I saw the stunning and fascinating exhibits I understood fully and appreciated the strength of the curatorial decisions made. I trust that the next Festival will be equally strong . . . and perhaps even have a "happy corner".

Where do you imagine your work in five years?

At my age, I hope I will still be working in five years. Although I feel young at heart, my body tells another story. I've had 8 joint replacements so far (with profound thanks to the taxpayers of Ontario), and decided with some sadness a couple of years ago to donate my wonderful 12-harness jack loom to OCAD. People still come to me for woven prayer shawls, but I've created them for 3 generations of several families, and so I can accept a graceful retirement in that area.

On the other hand, I think I'm a better designer now than at the beginning, and so I am enjoying creating a series of ketubot (wedding documents) inspired by textiles. The designs are licensed to a Toronto company that sells them world-wide (www.ketubah.com), and I receive handsome royalty cheques.